Book Club: Hegemony How-To by Jonathon Smucker

Hegemony How-To is an autobiography on running left-wing agitprop campaigns and a modern interpretation of the Long March through the Institutions. The author, Smucker, is an unsubtle communist who leans heavily on the work of Alinsky while quoting Gramsci. In a typically communist cliche, Smucker’s call to fame is his Schrödinger’s leadership status with Occupy Wall Street. What went well was our success; what didn’t was their failure.

Although not explicitly stated, the book’s essential premise is a path to power through the capture of culturally dominant institutions. This takes a formulaic approach:

- Organise a collective grievance against a specific target.

- Gather allies to support your cause while sabotaging and discouraging support for the target.

- Once a realistic threat is established, open a line of communication to negotiate.

- Achieve a meaningful concession, which furthers the group’s ability to exert influence and expand.

For example, consider an attack on a business’s reputation through accusations of racism. With the threat of a media storm, the stage is set for negotiation. The matter is then settled by employing a diversity and inclusion officer. This provides a job for a fellow true believer while also providing a foothold from which to further influence the company.

“A central argument of this book is that the larger social world (i.e., society) must always be our starting place and our touchstone. We have to meet people where they are at. The other side of this coin is that underdog groups have to vigilantly resist the tendency of insularity and self-enclosure.” -

AlinskySmucker

To use the masses, you need to speak in a language they understand, relative to viewpoints they currently hold, in a place they can hear you. As much fun as the telegram channels and matrix rooms are, sitting in a clubhouse does not lead to revolution or political capital. You must have a presence in the public sphere that is enticing, intelligible, and even respectable to a normie.

“Our work is not to build from scratch a special sphere that houses our socially enlightened identities (and delusions). Our work is, rather, to contribute to the politicization of presently de-politicized everyday spaces; to weave politics and collective action into the fabric of society.

…

Shifting the spectrum of allies is about moving people and groups—leaders, influentials, social bases, institutions, polity members, new and hitherto unmobilized actors, etc.—over just one notch closer to your position.”

It would not be true communism without entryism. Turning individual complaints into collective grievances is the bread and butter of democratic politics. This serves not just to rally the masses but also to create an angle of attack. A means of making the threat or crisis which will deliver the reward.

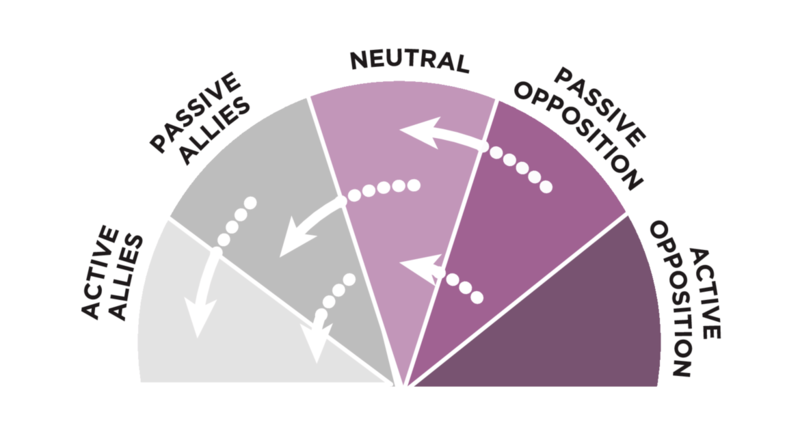

There is a strategic element to rallying the masses. Smucker recommends using a “spectrum of allies” diagram, which identifies the relevant groups, institutions, and leaders and places them in the appropriate ally -> opposition spectrum. The focus is then on how to shift each group one block closer to being an ally, supporting change or at least not actively working against you. For example, leveraging accusations of racism draws in recruits from anti-racism groups while discouraging others from defending your target.

“The group’s tactical options were constrained by the metonymic association of permits with the group’s story of the naïve liberal. Getting a permit might concretely help the group realize their tactical objective of attracting target demographics (i.e., families with children) to the protest, but this could not even be considered. To even suggest applying for a permit meant that you did not ‘get it’; you did not understand the problem of liberals and of ‘playing by the rules.’ Perhaps you did not really belong in the group.

…

We might, for instance, invoke the ‘iron law of oligarchy’ as a catchphrase that excuses us from having to take responsibility for the task of building political organization.”

In the same vein as thought-terminating cliches, some slogans express ideological commitment rather than effective tactics, advice or genuine caution. Letting these restrict your range of action is a pointless handicap; however, some care is needed. Often these exist to keep younger members from doing something stupid. Remember, no fed-posting.

“If we, political challengers, win an uphill struggle over meanings and narratives—if our values gain cultural hegemony and become the prevailing common sense—we have to extend the hegemonic contest beyond symbols, narratives, and meanings, and to move into the terrain of institutions, policies, and consolidation; to give political ’legs’ to our moral and cultural victories, in order to change social relations and material conditions.

…

The process of constructing common understandings, then, is inseparable from that of constructing dominant ideas.

…

By usurping the ‘officialization effect’ we were able to draw a lot of people who were not the ‘usual suspects’—folks who might have otherwise felt uncomfortable joining a fringe-seeming ‘protest’”

With each concession serving as a new foothold from which to gain the next concession, the end goal is the complete capture of the levers of power. The left-wing position of power within Academia gives them the means of shaping the next generation and a gatekeeper position for access to career-progressing credentials. From here, they leverage this position into private enterprise. Thus Cthulhu swims left.

“This is our challenge in the years ahead: to activate the unusual suspects. To do so, we have to develop leaders. They will emerge through concrete political struggles and campaigns that show everyday people that an organized collective force can win consequential battles.

…

Leadership and organization tend to develop hand in hand. The old organizer’s adage goes, ‘How do you identify leaders? They have followers.’”

A question followed me throughout this book: were these methods actually effective in achieving the author’s aims? The victories from movements like BLM were only possible with elite Democrat support, and arguably this elite were the primary benefactors. Nonetheless, this has aided the embedding of “Woke” ideas into government institutions, opening them up to the same subversion suffered by Academia. The begrudging conclusion is that these tactics have been successful despite their reliance on elite support.

There is room for these tactics to be deployed by the Right. The work of Chris Rufo follows the same pattern and has made gains against the left-wing presence in the American schooling system. These victories have similarly been mainly to the benefit of the Republican party. However, through the same game of concessions, there is an opportunity to embed new ideas and capture the party.

“Of course, most successful movements are first pronounced dead many times over.”